Copyright Infringement

LAWSUIT PRIMER Get an overview of the copyright lawsuit, including a timeline of the case, as well as downloadable pleadings made by the plaintiffs, CBS and Paramount, and defendants Alec Peters and Axanar Productions Inc. » Lawsuit Primer

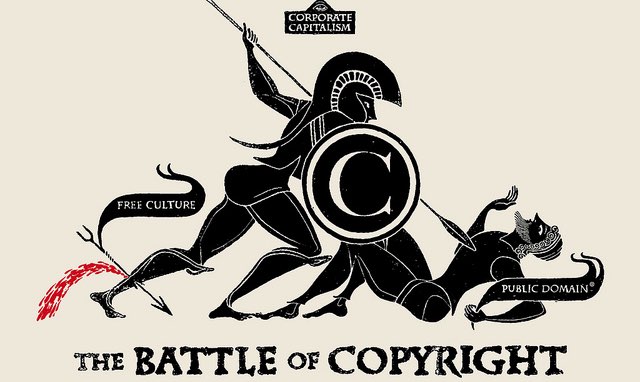

Depending what you read, the lawsuit that CBS and Paramount Pictures have brought against Axanar Productions is either David vs. Goliath, a battle over who gets to control Star Trek, fans trying to express their love for a treasured half-century old legend, soulless corporate greed threatened by plucky creatives or amateurs using intellectual property they don’t own to finance their foothold in the film industry.

At its heart, however, this dispute rests on whether Axanar engaged in copyright infringement against the Star Trek works owned by CBS Studios and Paramount Pictures.

What is infringement?

Copyright infringement is the use of works protected by copyright law without permission, infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, such as the right to reproduce, distribute, display or perform the protected work, or to make derivative works.

What Does Copyright Protect?

The copyright holder is typically the work’s creator, or a publisher or other business to whom copyright has been assigned. Copyright holders routinely invoke legal and technological measures to prevent and penalize copyright infringement.

Copyright infringement disputes are usually resolved through direct negotiation, a notice-and-takedown process (often referred to as a {!C&D:not an actual legal document; usually an attorney’s letter}}, or cease-and-desist), or litigation in civil court, even though infringement is technically a crime. Egregious or large-scale commercial infringement, especially when it involves counterfeiting, is sometimes prosecuted via the criminal justice system.

Legal Consensus

While the initial legal consensus was that Axanar was clearly infringing on the studios’ copyrights, the production’s pro bono representation by its law firm, Winston & Strawn, highlights how unsettled the law may actually be when it comes to the type of fan production Axanar claims to be.

Lincoln Bandlow, an attorney at Fox Rothschild LLP, summed up Axanar’s alleged infringement for the film industry journal, The Wrap:

“This appears to simply be the creation of a work based on characters and elements of the protected ‘Star Trek’ franchise. Essentially, Axanar appears to just be a situation where the producer is taking characters based on a well-known work because they know people love it. … With a small, not particularly commercial fan work … [the copyright holder] might simply say, ‘It’s not worth the time,’ said Bandlow. “But when you are going out and doing crowdfunding and making a million-dollar picture … that’s not going to be allowed.”1)

For its part, CBS issued a statement ascribing its problem with Axanar to the production operating as a professional, commercial venture:

“‘Star Trek’ is a treasured franchise in which CBS and Paramount continue to produce new original content for its large universe of fans. The producers of ‘Axanar’ are making a ‘Star Trek’ picture they describe themselves as a fully professional independent ‘Star Trek’ film. Their activity clearly violates our ‘Star Trek’ copyrights which, of course, we will continue to vigorously protect.”2)

Fan Films and Infringement

‘Axanar may be a turning point in the relationship between rights holders and fan fiction creators.’ — Jonathan Bailey, Plagiarism Today

Intellectual property lawyer Mary Ellen Tomazic, in her blog post, “Fan Films – Breaking the Unwritten Rules and Defining Profit,” describes the infringement of most fan productions as a harmless homage while highlighting the threat Axanar posed to CBS and Paramount:

Fan films use copyrighted material to pay homage to the original, and under the unwritten rules of this practice, they are not to be sold and no profit is to be made from them. … This noncommercial but still infringing use of copyrighted works is termed “tolerated use”, and is allowed by the rights holder despite knowing someone is infringing on their work.3)

“Sometimes a good thing can’t last,” writes Jonathan Bailey in an article, “How Money and Fame Have Changed Fan Fiction,” on his website, Plagiarism Today:

The truth is that Axanar may be a turning point in the relationship between rightsholders and fan fiction creators, a relationship that’s about to get a lot more complex. … The battle lines were being redrawn and the reason was because the Internet was, slowly, turning fan fiction and fan art into big business.4) [emphasis added]

Fan film producers have typically and explicitly acknowledged CBS as the copyright holder of Star Trek, and that their productions continue to exist at the studio's largesse. Even Axanar’s own website states this in its e-press center {!FAQ:Frequently Asked Questions}}:5)

Q.: How can Axanar Productions produce a Star Trek film without the backing of the rights holder?

A.: For the past few decades, Star Trek and a few other sci-fi franchises have enjoyed a cooperative/symbiotic relationship between fan-produced productions and the owners of the intellectual property. In general, CBS (the rights holder) allows independent Star Trek products as long as the venture is non-commercial. That means Axanar Productions can’t charge for anything featuring the Star Trek marks or IP and the finished film can never be sold as a movie, DVD/Blu-Ray, etc.6) [emphasis added]]

The trouble is, Bailey writes in Plagiarism Today, that fan work has inexorably become more and more commercial:

The commercial/non-commercial dichotomy has slowly been breaking down for fan creations. We are in a time where fan fiction authors will recast a fan fiction work as a new story for publication, seek to sell a fan-created lexicon or commercialize Let’s Play videos on YouTube. … Increasingly, any use can become a commercial one.8) [emphasis added]

Tomazic’s blog questions the way Axanar defines non-commercial:

The case revolves around what “profiting” from a fan film includes — can a filmmaker hire actors, set designers and build out a studio with crowdfunded money to make a “fan” film? Can he pay himself a salary from the funds? Paramount and CBS say no, deciding that this Axanar movie is no fan film but a competing product made from their copyrights and trademarks. The lawsuit is their way of reining in their previous tolerance of unlicensed use of their intellectual property, and protecting their legal rights under federal law.9)

Rules for the Future?

The eventual impact of this case, according to Tomazic, will limit what true fan productions can do in the future:

The Axanar lawsuit should serve as a cautionary tale for all fan film makers, as it will most likely result in strongly stated and probably strict parameters being set by other rights holders for future tolerated use of their intellectual property. Peters, by going too far in making a film that was no longer a fan film but a low-budget film with paid professionals competing with Star Trek works, crossed that line. He may have made it more difficult for fans to pay homage to their favorite movies with a lovingly crafted but still unauthorized work.10)

Indeed, Axanar producer Alec Peters had asked CBS and Paramount to more rigidly define what fan productions can and cannot do.11) Bailey, however, believes that is not likely to happen:

A fan creation [may] comply with the letter of the law but still be undesirable or even harmful to the original creation. … Rightsholders, almost universally, want flexibility when it comes to dealing with fan creations and, with that flexibility, comes uncertainty. We’re not likely to see many rightsholders laying down hard rules, save in specific areas, and that is going to create a great deal more fan-creator conflicts in the near future.12)

Defense

« Fair use is tricky; it is literally decided on a case-by-case basis by the courts. »

A number of limitations and exceptions exist to copyright related to a number of important considerations such as market failure, freedom of speech, education and equality of access (such as by the visually impaired). The most relevant to the Axanar case is the concept of fair use.

Fair Use

Fair use is a legal doctrine that permits limited use of copyrighted material without acquiring permission from the rights holders. It is one type of limitation and exception to the exclusive rights copyright law grants to the author of a creative work.

How to Determine Fair Use

Examples of fair use in U.S. copyright law include criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship or research, search engines, parody, teaching and library archiving. It provides for the legal, unlicensed citation or incorporation of copyrighted material in another author’s work under a four-factor balancing test:

- Purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.

- Nature of the copyrighted work.

- Amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.

- Effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

It should be noted, however, that fair use is tricky; it is literally decided on a case-by-case basis by the courts on the entirety of each set of circumstances. The same act done by different means or for a different purpose can gain or lose fair use status. Even repeating an identical act at a different time can make a difference due to changing social, technological, or other surrounding circumstances.13)

Axanar's Defense

See also: Knowing infringement?

According to its second motion to dismiss the lawsuit, Axanar’s evolving defense includes a claim of fair use.

Fair Use Defense

In fact, the dismissal motion appears to be setting up an eventual fair use defense on this basis:

To the extent any of the elements Plaintiffs are complaining about are actually protectable, Defendants intend to vigorously defend their use (if any) as a fair use. Without a film, the Court cannot evaluate the purpose and character of Defendants’ film, whether its nature is transformative or a parody, and the amount and substantiality taken (if any).

Under U.S. copyright law, these are three of the four factors courts must weigh when determining whether infringement constitutes fair use.14)

The defense omits the most important factor in determining fair use. Notably, the motion omits the fourth factor: commercial impact of the infringing use, which the Supreme Court ruled “is the single most important element of fair use,”15) and “must take account not only of harm to the original but also of harm to the market for derivative works.”16)

Portions of this article were adapted from the articles Copyright Infringement, Limitations and Exceptions to Copyright and Fair Use.

Keywords